Pharmaceutical Marketing Lessons Learned from the Crack Epidemic of the 80s

This week at The Guard Rail, we take a unique approach to marketing analysis. Instead of focusing on traditional advertising, we delve into a product that rapidly saturated the American market without a single paid ad campaign. By dissecting its distribution and cultural impact, we uncover how a dark chapter in U.S. history offers chilling lessons for modern public health and pharmaceutical strategy.

By Michael Bronfman, for Metis Consulting Services

Monday, November 10, 2025

When we think of marketing, we often picture glossy magazine ads, celebrity endorsements, or expensive television campaigns. But what happens when a product spreads nationwide without a single commercial, billboard, or corporate sponsor, yet still becomes one of the most recognized names in modern history? What can leaders in the pharmaceutical and public health fields learn from the story of crack cocaine? And how can what we learn be used to prevent harm?

In the 1980s and 1990s, crack reshaped American culture, fueled a violent underground economy, and led to some of the most severe drug laws ever enacted. Its rapid spread, dominance in the media, and creation of demand in communities that had never been affected by powdered cocaine all underscore the widespread impact of crack cocaine.

Was crack cocaine an example of the best marketing in modern history? And did the federal government, intentionally or not, help amplify its reach? To answer that, we need to look at what marketing truly means, how crack met every element of that formula, and what lessons the pharmaceutical and public health sectors can take from this dark and complex chapter.

What Marketing Really Means

At its foundation, marketing is more than advertising. It is described through the four Ps:

Product – What is sold

Price – How much does it cost?

Place – Where is it available?

Promotion – How people hear about it

A product does not need Madison Avenue to succeed. If it captures these four elements and meets real or perceived needs, it can spread rapidly. Crack cocaine, tragically, matched each of these elements with devastating accuracy.

The Product: Crack as a Chemical and Cultural Force

Powdered cocaine had long been associated with nightclubs, Wall Street, and Hollywood. It carried an image of wealth and status. Crack transformed that image by turning cocaine into a form that was accessible, powerful, and addictive.

By converting powdered cocaine into small smokeable rocks, dealers created a product with three dangerous traits:

Immediate effect – Smoking crack produced an intense, fast-acting high that snorting powder could not match.

Ease of use – The user required no syringes or complex preparation. A lighter and a simple pipe were enough.

Repeat demand – The short duration of the high created an immediate desire to use again.

From a product design perspective, crack was disturbingly effective. It was compact, easy to distribute, and designed to create repeat customers.

The Price: Cheap Enough for Everyone

Powdered cocaine was expensive, often costing hundreds of dollars for a night of use. Crack removed that barrier—a single hit costs as little as five or ten dollars.

This pricing model worked like a strategic plan, though one with deadly results:

Lowered entry cost – Anyone, regardless of income, could afford to try it.

Broadened customer base – People who could never access powdered cocaine suddenly had a stronger and cheaper alternative.

Created repeat buyers – The low price made it easy to return for more.

The price turned crack into a drug for the masses. Its accessibility was a key driver of its explosive growth.

The Place: Local and Immediate Availability

A product’s location determines how fast it spreads. Crack’s distribution model was direct, immediate, and local.

Street corners as retail space – Open-air markets made crack visible and convenient.

Apartments as distribution centers – Residential buildings became key supply points, embedding the trade within neighborhoods.

Constant supply – Users did not need to travel far or navigate formal systems; crack was always nearby.

This presence created an appearance of inevitability. In many cities, it became part of the urban landscape. From a marketing perspective, its availability strategy was flawless.

The Promotion: Media, Music, and Word of Mouth

Crack had no paid promotion, yet its visibility was unmatched. It spread through three dominant forces:

News coverage – Television news focused nightly on the so-called crack epidemic. Scenes of arrests, raids, and devastated families filled the screen. The constant exposure acted as free advertising, ensuring every household in America knew what crack was.

Music and culture – Hip hop in the 1980s and 1990s reflected the impact of crack on daily life. Artists spoke about the realities of addiction, poverty, and survival, unintentionally amplifying awareness.

Street communication – Word of mouth spread quickly. In many neighborhoods, everyone knew where to find crack and how powerful it was.

Promotion was viral long before digital media. Without spending a single dollar, crack became a national phenomenon.

The Federal Government’s Role

While dealers and users drove the market, the United States government also played a significant part in shaping the story. Some actions were deliberate, others unintentional, but together they magnified the attention crack received.

Harsh Sentencing Laws

In 1986, Congress enacted laws that punished crack possession one hundred times more severely than powdered cocaine. Five grams of crack carried the same penalty as five hundred grams of powder. These laws disproportionately impacted poor Black communities and reinforced crack’s reputation as America’s most dangerous drug.

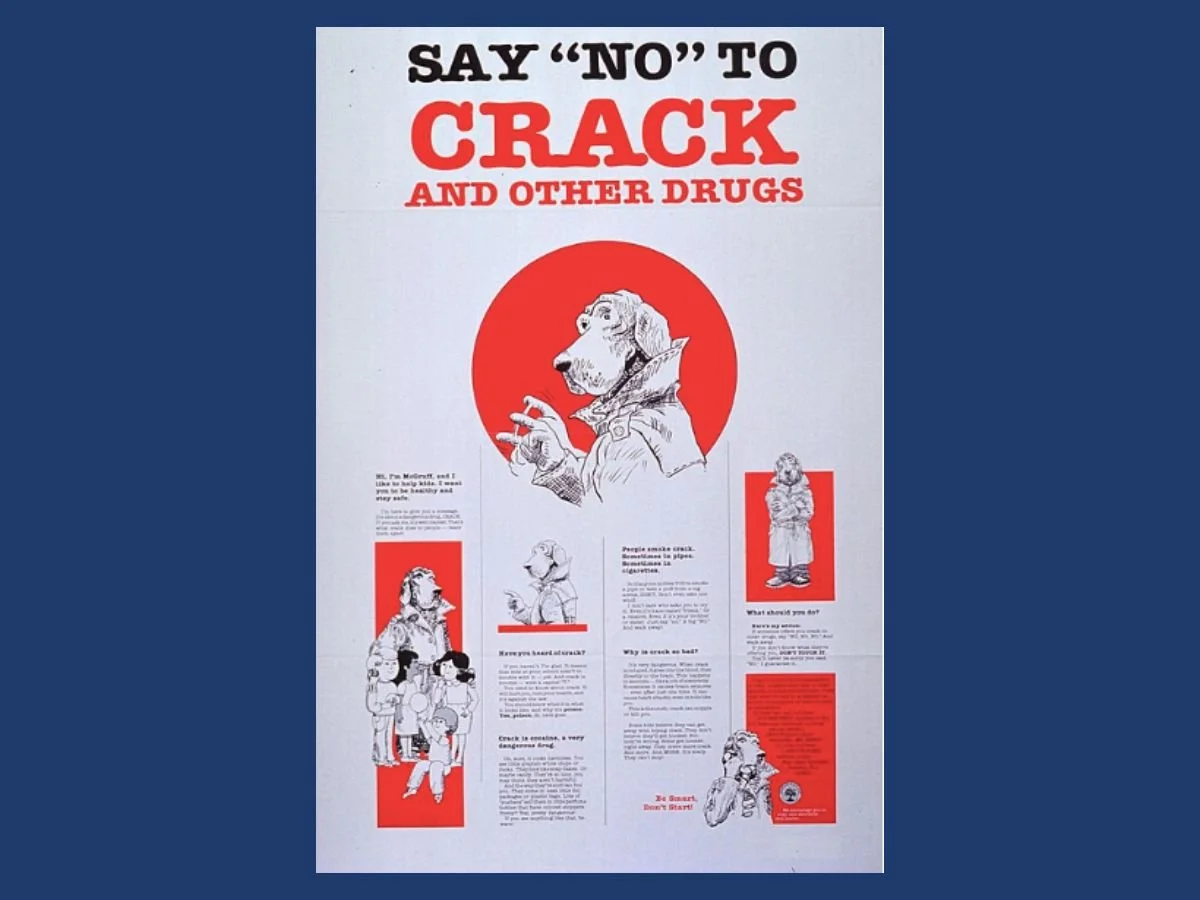

Publicity Campaigns

Government officials kept crack in the spotlight. Presidents displayed it during televised speeches. In one case, agents arranged a drug sale across from the White House so that a crack bag could be held up before cameras. What was meant as a warning became a national advertisement.

Foreign Policy and Perception

During the same era, the United States supported military operations in Latin America. Some cocaine traffickers had indirect connections to those operations. However, no evidence proved that the government intentionally spread crack; the perception that officials ignored it fueled lasting public suspicion.

Uneven Response

Instead of pairing enforcement with treatment and prevention, federal policy focused heavily on arrests and incarceration. This imbalance allowed addiction and violence to grow unchecked.

Together, these actions turned the government into an unintentional partner in amplifying crack’s visibility. Through continuous headlines and televised events, officials ensured that the drug remained at the center of public attention.

Why Crack’s Marketing Worked

Viewed through the lens of the four Ps, the reasons are clear:

Product – Potent, addictive, and easy to use

Price – Cheap and widely accessible

Place – Available everywhere, particularly in vulnerable communities

Promotion – Fueled by nonstop media coverage, music, and political attention

From a technical perspective, cracks spread resembles a marketing success story. But unlike legitimate products, its impact was devastating.

The Social Cost

The results were catastrophic:

Addiction – Families and communities were devastated by soaring dependency rates.

Violence – Crime and territorial conflict increased sharply as dealers competed for control.

Public health collapse – Overdose deaths, mental health breakdowns, and infectious diseases followed.

Mass incarceration – Sentencing laws targeted poor communities and left lasting social damage.

The apparent success of crack’s marketing came at an unbearable human cost.

Lessons for the Pharmaceutical and Public Health Sectors

Although tragic, the crack epidemic offers valuable lessons for healthcare leaders today:

Product design drives adoption – Crack’s formulation made it irresistible. In healthcare, the design and delivery of medicines, such as pills, patches, or injectables, strongly influence patient acceptance.

Price determines access – Low cost fueled crack’s spread. Conversely, high pharmaceutical prices prevent many patients from accessing essential treatments.

Availability shapes outcomes – Crack’s local accessibility drove high use. Making vaccines and therapies readily available within communities improves uptake.

Promotion must align with culture – Crack awareness grew through music and media. Effective public health campaigns must use cultural channels to reach real audiences.

Messaging matters – Sensational coverage of crack may have glamorized it. Public health communication must inform without glamor or shock.

Was It the Best Marketing Ever

If best means fastest, cheapest, and broadest reach, then crack cocaine stands as one of the most effective marketing phenomena in modern history. Yet calling it the best overlooks the devastation it caused.

A more accurate description is that crack was the most powerful underground marketing story of the late twentieth century, and its success came with an unbearable cost.

Crack cocaine never had a commercial, a billboard, or a spokesperson. Yet it spread across the United States more effectively than most legal products. It succeeded because it checked every marketing box: a potent product, a low price, constant availability, and relentless cultural visibility.

The federal government, through sentencing laws, publicity efforts, and foreign policy decisions, amplified its reach rather than containing it. These actions helped make crack a household name.

But the cost of that success was profound. Families collapsed, crack usage destroyed communities, and generations were lost to addiction and incarceration.

For leaders in the pharmaceutical and public health fields, the story of crack cocaine is not one to admire but one to analyze. It stands as a warning of what happens when the mechanics of marketing align with desperation and inequality. The real challenge is to use those same principles of product, price, place, and promotion to expand health, access, and equity rather than harm.

Share your thoughts on how these lessons can be applied constructively in today's healthcare landscape by reaching out to us directly: email us at hello@metisconsultingservices.com or stop by our website: Metisconsultingservices.com .

Key references

The rapid rise of the crack era:

“Between 1982 and 1985, the number of cocaine users increased by 1.6 million people.” Encyclopedia Britannica

“Crack, a smokable rock form of cocaine, became prevalent in the 1980s, especially among those of lower socioeconomic status as it was sold in small, cheap quantities (e.g. …).” PMC

“The crack epidemic in the United States refers to a significant surge in crack cocaine use that spanned from the early 1980s to the early 1990s. This form of cocaine could be sold in smaller quantities at a much lower price than powder cocaine.” EBSCO+1Availability, price, and socioeconomic conditions:

“This smokable rock form of cocaine … sold in small, cheap quantities … became prevalent in the 1980s, especially among those of lower socioeconomic status.” PMC

The article “The Setting for the Crack Era: Macro Forces, Micro Consequences” describes how structural economic decline, inner-city distress, and decreased opportunities in manufacturing upheld the environment in which crack flourished. PMCPromotion/media coverage and framing:

“Early news coverage of the rapid expansions and horrors associated with the use of crack in the mid-1980s led to a great panic.” PubMed

“Popular media coverage of the crack epidemic in the 1980s helped rile up enthusiasm for more punitive laws.” JSTOR Daily

“In the U.S., crack cocaine … the U.S. response to crack cocaine was driven by media depictions of an urban, public health crisis primarily affecting Black communities in American cities.” PMCGovernment/policy role:

“The 1986 bill created minimum sentencing laws with a 100:1 disparity between powder and crack cocaine …” HistoryLabs+1

“Federal laws were passed that imposed a 100:1 ratio on cocaine versus crack offenses …” O'Neill.

“A bill to provide an emergency Federal response to the crack cocaine epidemic through law enforcement, education and public awareness, and prevention.” (S. 2715, 1985-86) Congress.gov

The OIG report on “CIA-Contra-Crack Cocaine Controversy” gives details on alleged links between contras, CIA, and networks of cocaine/ crack supply. Office of the Inspector GeneralSocial cost: violence, crime, long-term effects:

“Using cross-city variation in crack’s arrival … we estimate that the murder rate of young black males doubled soon after these markets were established, … and their rate was still 70 percent higher 17 years later.” Andrew Young School of Policy Studies

“The crack epidemic had a host of new problems for the public health and drug treatment communities.” U.S. Government Accountability Office