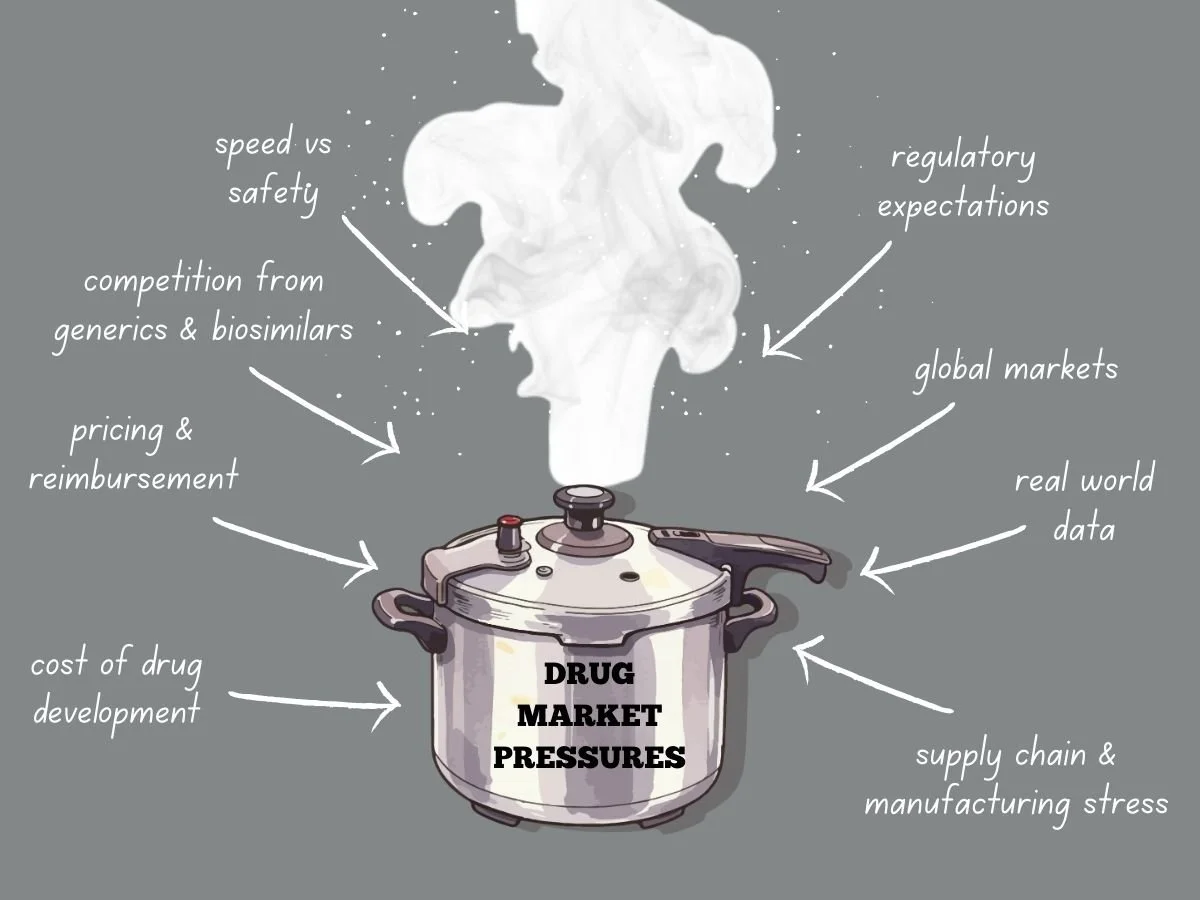

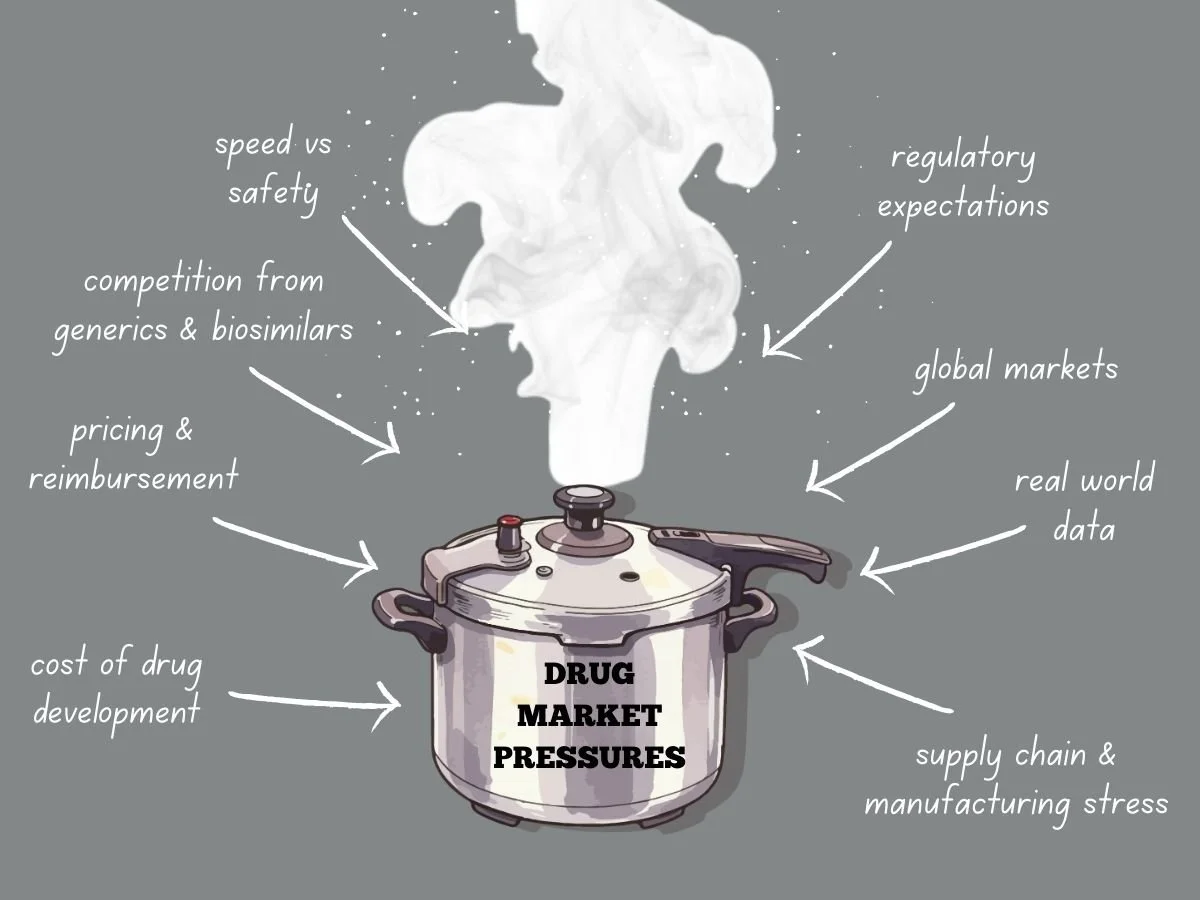

Navigating Intense Drug Market Pressures

Today’s global drug market faces more pressure than ever before. Pharmaceutical companies deal with higher development costs, tougher regulations, stricter pricing, and more competition from generics and biosimilars. Meanwhile, patients, payers, and governments want quicker access to safe and effective treatments. These factors are changing how companies plan, develop, launch, and manage products over time.

To succeed, companies need to know what causes market pressure and how it shapes their decisions. They also have to adjust their strategies while keeping quality, safety, and compliance intact.

This week in the Guardrail, we explore the intensifying economic and regulatory forces reshaping the global pharmaceutical landscape. We analyze the ways industry leaders can maintain compliance and quality while navigating the high-stakes pressures of modern drug development.

By Michael Bronfman for Metis Consulting Services

January 19, 2026

Today’s global drug market faces more pressure than ever before. Pharmaceutical companies deal with higher development costs, tougher regulations, stricter pricing, and more competition from generics and biosimilars. Meanwhile, patients, payers, and governments want quicker access to safe and effective treatments. These factors are changing how companies plan, develop, launch, and manage products over time.

To succeed, companies need to know what causes market pressure and how it shapes their decisions. They also have to adjust their strategies while keeping quality, safety, and compliance intact.

The Cost Reality of Drug Development

Developing new drugs is both costly and risky. It can take billions of dollars to bring a new medicine to market, especially when you include failed attempts. Clinical trials last for years, regulatory submissions need a lot of data, and manufacturing must meet rigorous quality standards.

As development costs go up, so does market pressure. Investors want to see returns, so leaders have to focus on programs most likely to succeed. This means making tough choices about which therapies to continue and which to pause or stop.

Pressure grows when competitors work on similar products. If a company is second to market, it can lose pricing power and market share. This pushes companies to find ways to develop products faster while still following the rules.

Pricing and Reimbursement Challenges

Pricing pressure is a major challenge in today’s drug market. Governments and private payers are resisting high launch prices, and value-based pricing is becoming more common. Companies now have to clearly show clinical benefits, real-world results, and economic value.

In the United States, pricing scrutiny continues to grow through policy changes and public debate. Programs like Medicare negotiation place additional pressure on manufacturers to justify pricing decisions. The NIH National Library of Medicine is a good resource for more information at https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11129567/

In Europe, pricing and reimbursement decisions are often made at the country level. Health technology assessments play a significant role in determining whether a product will be reimbursed and at what price. The European Medicines Agency provides regulatory approval, but market access depends on additional reviews. https://globalpricing.com/pricing-and-reimbursement-trends-in-europe-current-landscape-and-implications/

Because of these pressures, companies can not wait until after approval to plan for market access. They need to start early, thinking about evidence, comparators, and patient groups.

Competition from Generics and Biosimilars

Patent expiration is still a major source of market pressure. Once exclusivity ends, generics and biosimilars can quickly cut into revenue. Sometimes, prices fall by over 80 percent in the first year.

Companies have to plan their product life cycles early. They might consider new formulations, more uses, or combination products. Each choice needs careful regulatory planning and strong supporting data.

The US Food and Drug Administration provides guidance on generics and biosimilars, including approval pathways and exclusivity considerations at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/how-drugs-are-developed-and-approved.

Companies that wait too long to plan for the loss of exclusivity often have trouble protecting their product’s value when competitors arrive.

Speed Versus Safety

Market pressure often makes teams move faster. Quicker development can help patients get treatments sooner and improve a company’s position. But moving too fast without proper controls can lead to big risks.

Rushing trials can lead to poor study design or trouble enrolling patients. If data is incomplete, it can cause regulatory delays or extra work after approval. Cutting corners in manufacturing can cause quality problems and require more inspections.

To balance speed and safety, companies need strong oversight. Clear decision rules, teamwork across departments, and early talks with regulators are key. Programs that focus on quality from the beginning handle market pressure better.

Regulatory Expectations Do Not Ease Under Pressure

One common misconception is that regulators may be more flexible when market needs are urgent. While there are faster review programs, the standards for safety, effectiveness, and quality do not change for the Fast Track and Breakthrough Therapy designation. These programs aim to speed access while maintaining standards.

The FDA provides guidance:

But it can be tricky to navigate these expectations.

Using these pathways successfully requires careful planning and ongoing communication with regulators. Market pressure is not a good reason for weak data or incomplete submissions. This adds another layer of pressure. Regulatory requirements vary by region. Clinical trial designs must support multiple agencies. Manufacturing and labeling must meet diverse standards.

If regions are not aligned, it can cause delays and extra costs. For example, a trial designed just for the US might not work in Europe or Asia. Aligning global strategy early helps avoid these problems.

The International Council for Harmonisation plays a key role in aligning technical requirements across regions. Information on these guidelines is available at https://www.ich.org/page/search-index-ich-guidelines.

Understanding and applyLearning and using these guidelines early helps companies handle global market pressure better.

Global Markets Add Complexity

Many products are developed for global markets. This adds another layer of pressure. Regulatory requirements vary by region. Clinical trial designs must support multiple agencies. Manufacturing and labeling must meet diverse standards.

Misalignment between regions can lead to delays and added costs. For example, a trial designed only to meet US requirements may fall short in Europe or Asia. Early global strategy alignment helps reduce this risk.

The International Council for Harmonisation plays a key role in aligning technical requirements across regions. Information on guidelines is available at https://www.ich.org/page/search-index-ich-guidelines

Understanding and applying these guidelines early helps companies manage global market pressure more effectively.

Manufacturing Stress

Market pressure continues after approval. Manufacturing and supply chains have their own problems. It’s hard to predict demand, especially for new products. Shortages, global issues, and quality problems can all disrupt supply. Manufacturers to maintain control and continuity of supply. Inspections focus on data integrity, process validation, and change management. https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations

When under a lot of pressure, companies might try to stretch their capacity or put off investments. These choices often increase risk and can lead to regulatory problems.

The Role of Real World Evidence

As pricing and access decisions rely more on data, real-world evidence is becoming more important. Payers and regulators want to know how products work outside of controlled trials.

To collect good real-world data, companies need planning, the right systems, and oversight. They also have to meet regulatory standards for data reliability and privacy.

https://www.fda.gov/science-research

Companies that build these capabilities early are better able to handle market pressure and keep their products valuable over time.

Organizational Alignment Under Pressure

Market pressure often reveals weak spots in how organizations are set up. Gaps between clinical, regulatory, quality, and commercial teams can slow decisions. Conflicting goals can also cause teams to lose focus.

Successful organizations set shared goals and maintain open communication. They invest in training and clear processes. Leaders make it clear that compliance and quality always come first, even when deadlines are tight.

This kind of culture is essential when companies face inspections, audits, or public attention.

Looking Ahead

Drug market pressures are not going away. If anything, they will continue to intensify. Companies that treat pressure as a reason to cut corners will face setbacks. Those who use pressure as a driver for more thoughtful planning, stronger execution, and earlier collaboration will be better positioned to succeed.

Navigating this environment requires discipline, foresight, and respect for regulatory expectations. It also requires a clear focus on patients, who remain the ultimate reason these products exist.

The path from laboratory to patient has never been more complex, but you don't have to navigate these regulatory and economic hurdles alone. Contact Metis Consulting Services today. Learn how our strategic oversight and industry expertise can help your organization transform market pressure into a sustainable competitive advantage.

How AI Is Reducing Drug Development Timelines From Years to Months

Today, artificial intelligence (AI) is changing this story. With the help of AI, scientists and companies are finding ways to shrink drug development timelines from years to months. Reshaping the pharmaceutical industry can accelerate drug development, improve efficiency, and potentially increase the success of projects.

The traditional path to bringing life-saving medicine to market is a marathon that often spans over a decade. This week in the Guardrail, we explore how artificial intelligence is shattering these timelines, transforming a process that once took years into one that takes mere months

Written by Michael Bronfman for Metis Consulting Services

December 29, 2025

Developing new medicines has long been one of the slowest processes in science. In the traditional system, creating a new drug from the first idea to a product patients can use often takes ten to fifteen years, costs billions of dollars, and succeeds less than one in ten times. This long and expensive process leaves many patients waiting while the disease continues to cause suffering.

Today, artificial intelligence (AI) is changing this story. With the help of AI, scientists and companies are finding ways to shrink drug development timelines from years to months. Reshaping the pharmaceutical industry can accelerate drug development, improve efficiency, and potentially increase the success of projects.

In this article, we explain how AI is speeding up drug development, which stages of the process are changing most, and what this means for patients, scientists, and the future of medicine.

The Drug Development Timeline:

Before we explore AI, it is essential to understand the historical pathway of drug development. The process has multiple stages:

Target Identification: a molecule or biological process that is modifiable to treat a disease is identified by researchers.

Drug Discovery: Scientists design or find chemical compounds to interact with the target.

Preclinical Testing: To assess safety and efficacy, compounds are evaluated in cell and animal models.

Clinical Trials: If a compound is promising, it proceeds to human trials in three phases to assess safety and efficacy.

Regulatory Approval: Health authorities, such as the EMA and the FDA, review all data before approving a drug.

Each step can take years, especially clinical trials. Even after all this work, most drug candidates fail before approval. The combined effect is slow progress for patients and high costs for companies.

AI is now being used to transform nearly every stage of this timeline, thereby accelerating drug development and making it more predictable.

How AI Speeds Up Drug Development

Target Identification in Months Instead of Years

Target identification was once a lengthy, manual process involving laboratory experiments and trial-and-error. AI now allows researchers to analyze millions of data points from genetics, proteomics, and clinical records in hours or days rather than years. Machine learning models can identify potential biological targets much more quickly¹.

These advanced algorithms process data far faster than humans can and find connections that might be invisible in traditional research. Scientists can then decide which targets are worth pursuing months earlier than before, reducing the earliest phase of drug discovery from years to months².

AI Accelerates Lead Optimization

Once researchers have a target, the next step is to find compounds that interact with that target effectively and safely. In the past, this involved testing thousands of molecules in the lab. Now, AI can simulate molecule interactions in a computer, significantly shrinking the time needed for lead optimization³.

AI models can predict how changes to a molecule’s structure will affect its performance. These predictions reduce the amount of physical laboratory work required and help scientists focus on the most promising candidates first³. This step, which once took several years, can now be completed in a handful of months in some cases¹.

Predicting Outcomes Before Lab Tests Begin

AI can also forecast how a potential drug might behave in real biological systems. This capability enables researchers to assess toxicity, absorption, metabolism, and possible side effects in advance².

For example, deep AI models can now simulate aspects of human biology that once required years of animal testing or early human trials². These predictions help researchers avoid investing time in compounds likely to fail later. When AI rules out unworkable options early, it saves years of work and millions of dollars³.

Generative AI Is Designing Drug Candidates

Generative AI is a subset of Artificial Intelligence designed to create new molecules. This technology can generate tens of thousands of potential drug structures within hours, narrowing them down to the most promising options⁴.

Some of these AI-designed molecules are entering clinical trials much faster than traditional drug candidates. In one example, an AI platform developed a candidate and reached preclinical testing in 13 to 18 months, rather than the typical 2.5 to 4 years⁴.

Improving Success Rates in Early Trials

Traditional methods often yield a high failure rate before human testing begins. However, AI-assisted drug candidates exhibit substantially higher success rates in early clinical phases than conventional compounds⁵.

Industry studies report that AI-discovered candidates achieve Phase I success rates of 80–90%, compared with the industry average of 40–65%¹. These rates mean fewer setbacks and less time.

Faster Clinical Trial Design and Enrollment

AI is transforming clinical trials, which are among the most protracted and most expensive phases of development. By analyzing patient data, AI can more quickly identify the most suitable participants for a study⁶, thereby accelerating enrollment and increasing the likelihood that trials will yield meaningful results.

Other AI tools monitor patient data in real time and predict how participants may respond⁶. These tools can help researchers quickly adjust trial protocols, reducing months or even years from the clinical trial timeline⁶.

Real-World Examples of AI Cutting Timelines

AI Platforms Reducing Drug Development to Months

Some companies are already using AI to compress timelines dramatically. For example, a biotechnology firm developed a system that could shorten the stages of small-molecule drug development from months to two weeks for certain tasks⁷. That same system is projected to save one to one-and-a-half years before clinical trials start⁷.

Collaborations Between AI Firms and Big Pharma

Major pharmaceutical companies are partnering with AI startups to accelerate drug design. One collaboration between a U.S. biotech and a global pharmaceutical firm uses AI to produce drug candidates in three to four weeks from design to lab testing⁸.

These partnerships demonstrate that well-established pharmaceutical companies are adopting AI technologies to remain competitive and bring therapies to patients more quickly.

Why This Matters for Patients and Society

Faster drug development enables life-changing therapies to reach patients sooner. For patients with rare diseases or conditions for which there are no effective treatments, time saved in development is time saved from suffering. It also means that health systems could respond more rapidly to emerging disease threats, such as outbreaks or rising rates of chronic illness.

Accelerated development may reduce costs. When early failure is avoided and fewer resources are spent on unpromising candidates, resources are freed for investment in further research and development. These cost savings may eventually lower prices for patients, although this effect may depend on regulation and market forces.

Finally, increased efficiency may encourage greater investment in areas once considered too risky or too slow, such as treatments for neurological diseases or complex cancers.

Challenges and Realities

While AI is transforming drug development, we must remain grounded in reality. AI does not eliminate the need for human creativity, rigorous scientific validation, safety testing, or regulatory review. Human oversight remains essential in laboratory work, clinical trials, and data interpretation.

The future will involve proper regulation of AI tools to ensure they are safe, ethical, and transparent. But even with these limitations, the transformation AI brings is real and growing⁶.

Artificial intelligence is reshaping drug development in profound ways. From speeding target identification to optimizing molecules in silico, designing novel compounds with generative algorithms, and improving clinical trial outcomes, AI is making drug discovery faster, more innovative, and more efficient.

Instead of taking ten to fifteen years, new medicines are developed in a few years or even months. AI is not replacing scientists. Instead, it is amplifying their abilities, allowing them to focus on high-impact decisions while machines handle routine, data-intensive tasks. This partnership promises a future where better medicines reach patients sooner, with greater success, and at lower cost.

The era of AI-powered drug development has begun, and it will transform how medicines are developed for decades to come.

Ready to accelerate your innovation? The future of pharmaceutical efficiency isn’t just about better data—it’s about better strategy. Discover how our expertise can help your organization lead the next generation of medical breakthroughs. Contact us today hello@metisconsultingservices.com

Footnotes

All About AI – AI in Drug Development Statistics 2025

https://www.allaboutai.com/resources/ai-statistics/drug-development/World Health AI – Drug Discovery Accelerates Development

https://www.worldhealth.ai/insights/drug-discoverySimbo AI – The Future of Drug Discovery

https://www.simbo.ai/blog/the-future-of-drug-discovery-how-ai-is-accelerating-development-timelines-and-improving-efficiency-in-pharmaceutical-research-467406/

Understanding the Significance of CRLs Being Released: Beyond the Regulatory Language

The FDA's Complete Response Letter (CRL)-- few documents hold as much weight in the complex and often opaque world of pharmaceutical development, as the CRL. Metis Consulting can help navigate them, learn more at our blog, The Guard Rail.

Written by Michael Bronfman, July 28, 2025

This week in The Guard Rail, we at Metis are looking at a hot topic for our industry. Michael Bronfman tackles a hidden power in the pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturing world: the FDA's Complete Response Letters (CRLs). These are not just dry documents. The contents have traditionally been kept secret, known only to the receiving company. However, that secrecy might now be coming into the open. Why? Because a CRL can instantly derail a company's future, send stock prices plummeting, and, most critically, determine if a life-saving treatment ever sees the light of day. Join us as we uncover why these once-confidential letters are at the heart of a tidal wave push for transparency.

The FDA's Complete Response Letter (CRL)-- few documents hold as much weight in the complex and often opaque world of pharmaceutical development, as the CRL. For many outside the industry, the term might sound dry, bureaucratic, or even cryptic. But for drug developers, investors, patients, and clinicians, CRLs are pivotal turning points; letters that can reshape company strategy, impact stock prices overnight, and, most importantly, influence when or even if a new therapy reaches patients.

Historically, the contents of CRLs have often remained confidential, known only to the company receiving them and occasionally, selectively disclosed to the public. Yet the idea of CRLs being more broadly released, whether voluntarily by sponsors or systematically through policy change has gained traction. Why? Let us explore why these letters matter, what they contain, and why making them public can be a significant step forward for science, business, and patient trust.

What exactly is a CRL?

A Complete Response Letter is issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) when it completes its review of a New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA) but decides not to approve it in its current form. Importantly, a CRL does not mean the drug is permanently rejected. Instead, it outlines the deficiencies that prevent approval and often provides guidance on what the sponsor could do to address them.

Deficiencies can include:

Issues with clinical efficacy or safety data (e.g., not enough evidence that the drug works, or safety concerns in certain patient populations)

Manufacturing or quality control shortcomings

Problems with labeling or risk management strategies

Statistical or methodological issues in trial design

For sponsors, receiving a CRL is both a setback and a roadmap. It’s an official document telling them: “Here is what is missing; come back when you have fixed it.”

The FDA's Complete Response Letter (CRL) few documents hold as much weight, in the complex and often opaque world of pharmaceutical development, as the CRL. For many outside the industry, the term might sound dry, bureaucratic, or even cryptic. But for drug developers, investors, patients, and clinicians, CRLs are pivotal turning points; letters that can reshape company strategy, impact stock prices overnight, and, most importantly, influence when or even if a new therapy reaches patients.

Historically, the contents of CRLs have often remained confidential, known only to the company receiving them and occasionally, selectively disclosed to the public. Yet the idea of CRLs being more broadly released — whether voluntarily by sponsors or systematically through policy change — has gained traction. Why? Let's explore why these letters matter, what they contain, and why making them public can be a significant step forward for science, business, and patient trust.

What exactly is a CRL?

A Complete Response Letter is issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) when it completes its review of a New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA) but decides not to approve it in its current form. Note, a CRL does not mean the drug is permanently rejected. Instead, it outlines the deficiencies that prevent approval. Often, the letter will provide guidance on what the sponsor can do to address the issue.

Deficiencies can include:

Issues with clinical efficacy or safety data (e.g., not enough evidence that the drug works, or safety concerns in certain patient populations)

Manufacturing or quality control shortcomings

Problems with labeling or risk management strategies

Statistical or methodological issues in trial design

For sponsors, receiving a CRL can be a setback, but it is also can be a roadmap. It is an official document that says: "Here is what is missing; come back when you have fixed it."

Why are CRLs so important?

CRLs carry enormous significance because they sit at the intersection of science, business, and public health. Consider:

1. Strategic pivot points for companies

A CRL forces a company to decide: Do we invest more time and money to address the FDA's concerns, or do we walk away? Sometimes the deficiencies are minor and easily fixable; at other times, they are so fundamental that continuing to do so makes little sense.

2. Market-moving disclosures

Because the market places great value on new product approvals, the news of a CRL often leads to sharp drops in a company's stock price — especially if the drug was seen as a major pipeline asset.

3. Impact on patients

For patients waiting for new treatment options, CRLs can feel like an unexpected delay. Understanding the nature of the deficiency can help patients and advocates see whether it is a temporary hurdle or a sign of deeper problems.

4. Scientific learning

Each CRL is a detailed FDA critique of a drug's data and the sponsor's responses. While usually kept confidential, if shared, they can become case studies that improve drug development as a whole.

The current situation: Confidential by default

Under U.S. law, CRLs are part of a company's regulatory correspondence and thus are treated as confidential commercial information. Sponsors may choose to disclose the fact that they received a CRL — and often do, given that it's material information for investors — but the actual content is rarely released in full.

Instead, companies often issue press releases summarizing the FDA's concerns. Unfortunately, these summaries can be selective, vague, and overly optimistic:

Selective: emphasizing easily fixable manufacturing issues and omitting more serious efficacy concerns

Vague: using language like "additional analyses requested" without context

Optimistic: framing the CRL as "a minor setback" even if the letter itself is more critical

This practice makes it hard for outside observers — including investors, clinicians, and patient groups — to understand what really happened.

The significance of CRLs being more publicly released

CRLs regularly released in full, could have a profound effect on how new therapies are evaluated, understood, and debated. Here's why:

1. Transparency builds trust

Our industry struggles with perceptions of secrecy. Polished summaries are shared and that is fine but if they are the only data released, it is impossible to know if the sponsor is downplaying serious concerns. Releasing more complete CRLs shows the unfiltered FDA perspective, which can reassure the public that approvals are based on thorough, science-driven review.

2. Better information for stakeholders

Investors could better assess the real risk of resubmission and approval. Clinicians could understand why certain drugs were not approved — whether due to safety concerns in specific populations or inadequate evidence of benefit. Patients and advocacy groups could advocate more effectively if they knew the precise barriers.

3. Industry-wide learning

Drug development is full of repeated mistakes: inadequate trial design, poor endpoint selection, underpowered studies, or manufacturing gaps. Public CRLs can serve as detailed case studies, allowing future sponsors to avoid similar pitfalls.

4. Accountability

Public CRLs help ensure that sponsors fully address the FDA's concerns before resubmitting, rather than trying to sidestep them with minimal new data. They also keep the FDA accountable, making its reasoning transparent and open to scientific debate.

Potential drawbacks and industry concerns

Of course, releasing CRLs is not without controversy. Key concerns include:

1. Proprietary data

CRLs often contain detailed discussion of clinical trial data, manufacturing processes, and commercial plans. Sponsors argue that full disclosure could benefit competitors or harm competitive advantage.

2. Misinterpretation

FDA reviews are technical documents, and taken out of context, statements in a CRL could be misread by the public or sensationalized by the media.

3. Chilling effect on communication

If sponsors know that every word in their submissions could become public, they might be less candid, potentially limiting open dialogue with regulators.

4. Impact on innovation

Some fear that too much transparency could discourage small biotech firms — already operating under tight timelines and budgets — from pursuing high-risk programs.

The evolving conversation

The debate is not purely academic. In recent years:

Some sponsors have voluntarily released CRLs, especially when the market reaction to vague summaries was worse than anticipated.

Regulatory advocates and transparency groups have pushed for routine publication, arguing that CRLs, like European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs), could help demystify the approval process.

The FDA itself has signaled interest in improving transparency, though it is constrained by existing confidentiality laws.

The conversation reflects a broader trend in medicine: moving from "trust us" to "show us." Patients, payers, and clinicians want to see the data and the reasoning behind it, not just the headline.

International context

The U.S. FDA is not alone in grappling with this issue. European regulators, through the EMA, publish relatively detailed assessment reports once a drug is approved, but not if it is rejected. Similarly, Health Canada has taken steps to publish "Summary Basis of Rejection" documents for drugs that are not approved.

These models demonstrate that it is possible to balance transparency with the protection of confidential information, although it requires careful policy design.

A path forward

So, what would be the ideal outcome?

Routine publication of redacted CRLs: Share the FDA's reasoning while redacting truly proprietary data, like detailed manufacturing process steps.

Standardized summaries: Even if full letters aren't released, require sponsors to issue standardized, FDA-reviewed summaries that accurately reflect the deficiencies.

Educational context: Provide plain-language explanations alongside CRLs, so clinicians, patients, and journalists can understand the technical details.

Such steps could bring real benefits without undermining innovation.

Why it matters

At its heart, the significance of CRLs being released is about more than a document. It is about shining light on critical moments in the life of a new therapy: the point where data meets judgment. When companies keep those moments private, the public can only guess at what went wrong. When CRLs are shared, everyone from researchers designing the next trial to patients hoping for a breakthrough can see, learn, and plan accordingly.

Transparency is not a cure-all. It won't eliminate uncertainty, disappointment, or risk. However, in a field where trust is essential and decisions affect both lives and balance sheets, sharing the FDA's reasoning is a powerful way to build confidence, foster learning, and ultimately bring better medicines to the people who need them.

If your organization is grappling with CRLs or needs help avoiding them, please contact us at Metis Consulting Services: Hello@MetisConsultingServices.com.

For more info, see our website www.MetisConsultingServices.com

What We Lose by Cutting Research Funding in the U.S.A.

For decades, the United States has led the world in biomedical innovation, powered by long-term investment in public research infrastructure. Institutions like the NIH, NSF, and CDC have been cornerstones of medical progress and global health preparedness. But that leadership is slipping. Research budgets are flattening or declining in real dollars, while political instability further threatens their continuity.

By Michael Bronfman, June 10, 2025

Author assisted by AI

This week, The Guard Rail is proud to feature a crucial topic impacting the very foundation of innovation in the pharmaceutical and life sciences industries. This comes on the heels of ongoing discussions about the importance of sustained investment in research and development. Our latest post, "What We Lose by Cutting Research Funding in the U.S.A.," delves into the far-reaching consequences of diminishing public funding for scientific endeavors. Please let us know what you think.

Science isn’t self-sustaining. It needs fuel, and that fuel is funding.

For decades, the United States has led the world in biomedical innovation, powered by long-term investment in public research infrastructure. Institutions like the NIH, NSF, and CDC have been cornerstones of medical progress and global health preparedness. But that leadership is slipping. Research budgets are flattening or declining in real dollars, while political instability further threatens their continuity.

In biopharma, where product pipelines rely on early-stage discovery science, this isn’t just a government problem. It’s an industry crisis in the making.

Slower Drug Discovery and Development

Fact: Every one of the 210 new drugs approved by the FDA between 2010 and 2016 was linked to publicly funded research. Biopharma companies rely on foundational science to guide their pipelines, but they rarely fund that science directly. The risk is too high and the payoff too far off. It’s public institutions that decode disease mechanisms, identify new drug targets, and lay the groundwork for innovative therapies.1

Cuts to NIH funding don’t just slow university research—they erode the pipeline feeding the next generation of breakthrough medicines.

Weakened Global Competitiveness

STAT: China now leads the world in total scientific publications and is rapidly closing the gap in high-impact research.(Source: Nature Index, 2023)2 While U.S. funding stagnates, China and the EU are aggressively investing in research. China, in particular, has made biomedical innovation a national priority, pouring billions into AI in drug discovery, gene editing, and translational medicine. As funding dries up at home, U.S. scientists—especially early-career researchers—are lured by more stable prospects abroad. That includes faculty appointments, lab funding, and full-stack innovation ecosystems. Innovation is global. If the U.S. doesn’t lead, someone else will.

Loss of Talent and the “Leaky Pipeline”

STAT: Less than 17% of U.S. biomedical PhDs secure tenure-track positions.(Source: NIH Biomedical Workforce Report, 2021)

“Nowadays, less than 17% of new PhDs in science, engineering and health-related fields find tenure-track positions within 3 years after graduation (National Science Foundation, 2012; Chapter 3). Many PhDs who do not find tenure-track positions turn to positions outside academia. Others who think that they will have better future opportunities accept relatively low-paying academic jobs such as postdoctoral positions and stay in the market for a prolonged period (Ghaffarzadegan et al., 2013). Many engineering PhDs go the entrepreneurial route and become involved in startups or work in national research labs or commercial R&D centres. But our focus is academia.”

Science takes a long time. Researchers spend over a decade training before leading independent labs. But the bottleneck isn’t talent—it’s funding.

When grant paylines fall and budgets shrink, postdocs and junior faculty face fewer opportunities. Many leave academia entirely. Others go overseas. This brain drain disproportionately impacts women and underrepresented minorities, who face systemic disadvantages and less funding security.

Losing these scientists means losing not just skill, but diversity of thought—and long-term industry innovation.

Fewer Breakthroughs in Rare and Neglected Diseases

STAT: 50% of rare disease research projects rely heavily on NIH funding. (Source: NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research)3 Pharma’s ROI models don’t always support research in areas with small patient populations. Rare diseases, neglected tropical illnesses, and pediatric cancers often fall outside commercial viability. Public funding fills this gap—fueling the early science, infrastructure, and data that eventually enable therapies. The first gene therapies, mRNA vaccines, and targeted oncology platforms were born out of public research on “unprofitable” conditions. Cutting funding abandons these patients—and the innovation that often follows from solving hard, overlooked problems.

Delayed Preparedness for Future Pandemics

STAT*: NIH invested over $700M in coronavirus research before COVID-19 emerged.(Source: Congressional Research Service, 2021)4 The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines didn’t happen overnight. It was built on decades of NIH-funded virology, structural biology, and RNA delivery research. Agencies like BARDA and DARPA took the financial and technological risks long before private companies stepped in. The Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines succeeded because the science—and the funding—was ready. Cutting infectious disease research now will leave us vulnerable to the next pandemic. Public health readiness can’t be “turned on” in a crisis—it must be sustained year-round.

A Fragile Clinical Trial Ecosystem

STAT: Over 40% of U.S. clinical trials are led or supported by NIH, VA, or academic medical centers.(Source: ClinicalTrials.gov data analysis, 2023)

“The claim that over 40% of U.S. clinical trials are led or supported by the NIH, VA, or academic medical centers is supported by multiple sources.

NIH's Role in Clinical Trials

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the largest funder of biomedical research in the United States. In 2024, more than 80% of its $47 billion budget was allocated to support research, including clinical trials, at over 2,500 scientific institutions. Notably, 60% of this extramural research occurred at academic medical center campuses. (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, aamc.org)

VA's Contribution to Clinical Trials

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) also plays a significant role in clinical research. Through its Office of Research and Development, the VA supports numerous clinical trials. As of November 2023, approximately 932,000 veterans were enrolled or expected to be enrolled in studies funded by the VA. (en.wikipedia.org, congress.gov)

Academic Medical Centers and Clinical Trials

Academic medical centers are integral to the U.S. clinical trial landscape. Institutions like Massachusetts General Hospital and Stanford University collaborate with the VA and NIH, contributing to a substantial number of clinical trials. (journals.lww.com)”

Private pharma drives large-scale, late-phase trials. But early-phase, rare disease, and non-commercial trials rely heavily on public funding and academic infrastructure.

From the Cancer Moonshot to the All of Us initiative, federal investment creates platforms and protocols that benefit the entire ecosystem. Without that scaffolding, trials become slower, more expensive, and riskier for sponsors.

When government funding falters, it’s not just public labs that lose—it’s the entire translational pipeline.

Reduced Return on Public Investment

STAT: Every $1 of NIH funding generates over $8.38 in economic activity.(Source: United for Medical Research, 2020)6 Research isn’t charity, it’s investment. From university spinouts to biotech accelerators, public science creates real economic value. This includes IP generation, job creation, tax revenue, and long-term cost savings in healthcare.

Cutting research funding doesn’t save money—it sacrifices return. And once lost, scientific momentum is hard to regain. Labs close. Talent relocates. Innovation stalls.

We’re not just undermining future therapies—we’re eroding the base of an entire innovation economy.

Erosion of Scientific Literacy and Trust

STAT: Public trust in science has dropped by 10+ points since 2020, especially among younger (U.S.) Americans.(Source: Pew Research, 2023)7

Public research supports more than lab benches—it funds data-sharing, transparency, education, and outreach. From open-access journals to science museums and K–12 programs, public science is a social good.

Without investment, we lose more than knowledge. We lose shared understanding. That void gets filled by misinformation, distrust, and anti-scientific sentiment—especially in an era of rapid technological change.

A well-funded, transparent research ecosystem builds trust, and trust saves lives

Final Thoughts: Innovation Requires Stability

Cutting research funding may seem like a short-term budget fix. But the long-term cost is far higher.

We lose:

Therapies that never make it to trials.

Scientists who leave the field.

Competitive edge in a global biotech arms race.

Preparedness for emerging diseases.

Public trust in health science.

The U.S. has always been a leader because it invested in being one. That’s not guaranteed. Leadership in science is a choice—a policy decision. One that affects every sector of pharma, from discovery to market.

If you’re in biopharma, policy, or research, your voice matters.

Support stable, bipartisan investment in:

NIH, NSF, and BARDA budgets

Early-career research funding

Open science infrastructure

Translational and rare disease initiatives

Let’s ensure the U.S. remains a place where great science thrives—and where public funding continues to fuel private innovation for decades to come.

Let’s continue the conversation.

What impact have you seen from federal research funding in your work? What do we risk losing? Drop a comment or share this post to keep science at the center of policy.

1. PNAS study on NIH-funded research and drug approvals(Source: Cleary et al., PNAS, 2018)

2 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-01867-4

3. https://hr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/public/documents/2022-07/ohr-annual-report-2021.pdf

5. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9975718/

6. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/budget https://unitedformedicalresearch.org/annual-economic-report/